Identifying the 5 Translations

And reporting the results of the Genji translation poll

Here are the results of yesterday’s poll concerning the readers’ preferences regarding the five translations of GENJI MONOGATARI.

46% Translation 2

33% Translation 1

07% Translation 3

07% Translation 4

06% Translation 5

Translation 2 was the winner by a mile, being the preference of nearly half of the human readers taking part. This is remarkable, for reasons that will soon become clear. But first, it might interest those of you who participated in the translation poll yesterday to see how two of the more powerful AI systems judged the various translations, keeping in mind that they also reached their conclusions without knowing anything about the identity of the translations. Both were provided the same sections displayed yesterday as well as the original text for the purposes of analysis.

CLAUDE 4.5 SONNET

Brief Summaries of Each Translation

Translation #1: A formal, early-20th-century rendering that closely follows the original’s social hierarchy and allusions, albeit with occasional Edwardian embellishments. Its prose is ceremonious and immersive but may feel dated.

Translation #2: A modern literary adaptation that emphasizes psychological depth and vivid metaphor. It reads like contemporary fiction, taking creative liberties to enhance emotional resonance, sometimes at the expense of literal accuracy.

Translation #3: A clear, concise, and modern translation that prioritizes accessibility. It faithfully conveys plot and relationships but simplifies nuanced descriptions and cultural specifics.

Translation #4: A scholarly yet elegant translation that carefully preserves original terms, nuances, and narrative tone. Supported by footnotes, it balances accuracy with fluid prose, making it an excellent choice for both study and reading.

Translation #5: An explanatory translation that ensures comprehensibility through occasional paraphrasing and added context. It is faithful in content but tends to be verbose and less stylistically distinctive.

Ranking by Fidelity to the Original

Translation #4 – Demonstrates meticulous accuracy in rendering titles, social nuances, and narrative tone. It adheres closely to the original syntax and meaning, often supplementing with scholarly footnotes for clarity.

Translation #1 – Faithful to the original, though it occasionally employs archaic English equivalents and mild embellishments (e.g., “secretly hoped”) that slightly depart from the text.

Translation #3 – Concise and accurate, but simplifies some complex descriptions and cultural subtleties for readability.

Translation #2 – Captures the emotional core but takes significant interpretive liberties, adding metaphors and psychological explanations not present in the original.

Translation #5 – Tends to paraphrase and expand with explanatory phrases, sometimes sacrificing precision for clarity.

Ranking by Literary Quality

Translation #2 – Exceptionally vivid and lyrical, with novelistic flourishes and powerful imagery. It reads as compelling modern literature, though its style is decidedly interpretive.

Translation #4 – Elegant, balanced, and clear. Its prose is both precise and fluid, effectively evoking the Heian court without archaic stiffness.

Translation #1 – Formal and stately, with a classic early-20th-century style that suits the tale’s atmosphere.

Translation #3 – Straightforward and accessible, but lacks distinctive stylistic character.

Translation #5 – Competent but occasionally wordy, with less rhythmic flow and polish than the others.

DEEPSEEK

Translation 1

Fidelity: Moderate. Captures the essential narrative but takes liberties with phrasing. The parenthetical “(he lived it matters not when)” is an interpolation that domesticates the original’s more neutral temporal vagueness. Some elaborations (”petty vexations,” “willy-nilly”) add color not strictly present in the source.

Literary Quality: Edwardian in register, with a courtly, slightly antiquated diction (”preponderant,” “barons and courtiers,” “Land Beyond the Sea”). The prose is fluent but occasionally verbose. The phrase “a close bond had joined them” for the Buddhist karmic connection is vague.

Reader Appeal: Accessible to readers comfortable with early 20th-century English prose. The style may feel dated to contemporary readers, and certain choices (e.g., “man-child”) are archaic.

Translation 2

Fidelity: Moderate. This is the freest of the five translations, frequently departing from literal meaning to pursue effect. Phrases like “a jewel made flesh,” “the metal was soft and the blows kept coming,” and “a treasure, not an obligation” are interpretive expansions. The translator prioritizes emotional texture over strict accuracy.

Literary Quality: The highest among the five in terms of contemporary literary craft. The prose is muscular, image-driven, and emotionally immediate. Sentences like “She wrapped herself in it like armor, though the metal was soft and the blows kept coming” are striking. The rhythm is controlled, the diction modern without being colloquial.

Reader Appeal: Likely the most appealing to educated readers seeking literary engagement rather than scholarly fidelity. The translation reads as a confident work of English prose.

Translation 3

Fidelity: High. Closely tracks the original’s content and sequence. Phrasing like “a jewel beyond compare” for 玉の男御子 is accurate. The translator resists interpolation and maintains a neutral scholarly tone.

Literary Quality: Competent but restrained. The prose is clear and readable but lacks rhythmic distinction. Sentences tend toward the declarative and can feel flat. “The sad fact was that the girl was without strong backing” is accurate but prosaic.

Reader Appeal: Suitable for readers who prioritize accuracy over style. The translation serves the text faithfully but does not seduce.

Translation 4

Fidelity: High, with careful attention to nuance. The translator preserves ambiguity where it exists in the original and avoids over-interpretation. The footnote reference to “Yōkihi” (Yang Guifei) indicates scholarly apparatus. Phrases like “His Majesty must have had a deep bond with her in past lives as well” render the Buddhist implication accurately.

Literary Quality: Solid but somewhat formal. The prose has a measured, dignified quality appropriate to the courtly subject. However, it occasionally feels stiff or bureaucratic (”His insistence on keeping her with him despite her fine reputation”).

Reader Appeal: Appeals to readers who want fidelity combined with readability. The formality may distance casual readers.

Translation 5

Fidelity: Moderate to high. Generally accurate, though the opening—”IN WHOSE reign was it that a woman of rather undistinguished lineage captured the heart of the Emperor”—adds an interrogative emphasis not quite present in the original’s more neutral いづれの御時にか. The translation of bureaucratic and ritual terms is careful.

Literary Quality: Competent but uneven. The prose is clear and sometimes elegant (”a pure radiant gem like nothing of this world”), but other passages are awkward (”anxiety she suffered as a consequence of these ever-increasing displays of jealousy was such a heavy burden that gradually her health began to fail”—overlong and syntactically clumsy).

Reader Appeal: Serviceable for general readers but lacks the polish to fully engage literary audiences.

Literary Quality

Translation 2 — Strongest as a work of literary prose

Translation 1 — Accomplished in an older register; fluent if dated

Translation 4 — Dignified but occasionally stiff

Translation 3 — Competent but flat

Translation 5 — Uneven; some clumsy constructions

Overall Preference (educated English reader)

Translation 2 — Most likely to engage literary readers

Translation 4 — Balanced fidelity and readability; satisfies dual demands

Translation 1 — Appeals to readers who enjoy period style

Translation 3 — Reliable but not memorable

Translation 5 — Least distinctive; neither especially faithful nor stylish

The translations were as follows:

Translation 1 = Arthur Waley 1933

Translation 2 = Castalia House 2025

Translation 3 = Edwin Seidensticker 1973

Translation 4 = Royall Tyler 2009

Translation 5 = Dennis Washburn 1999

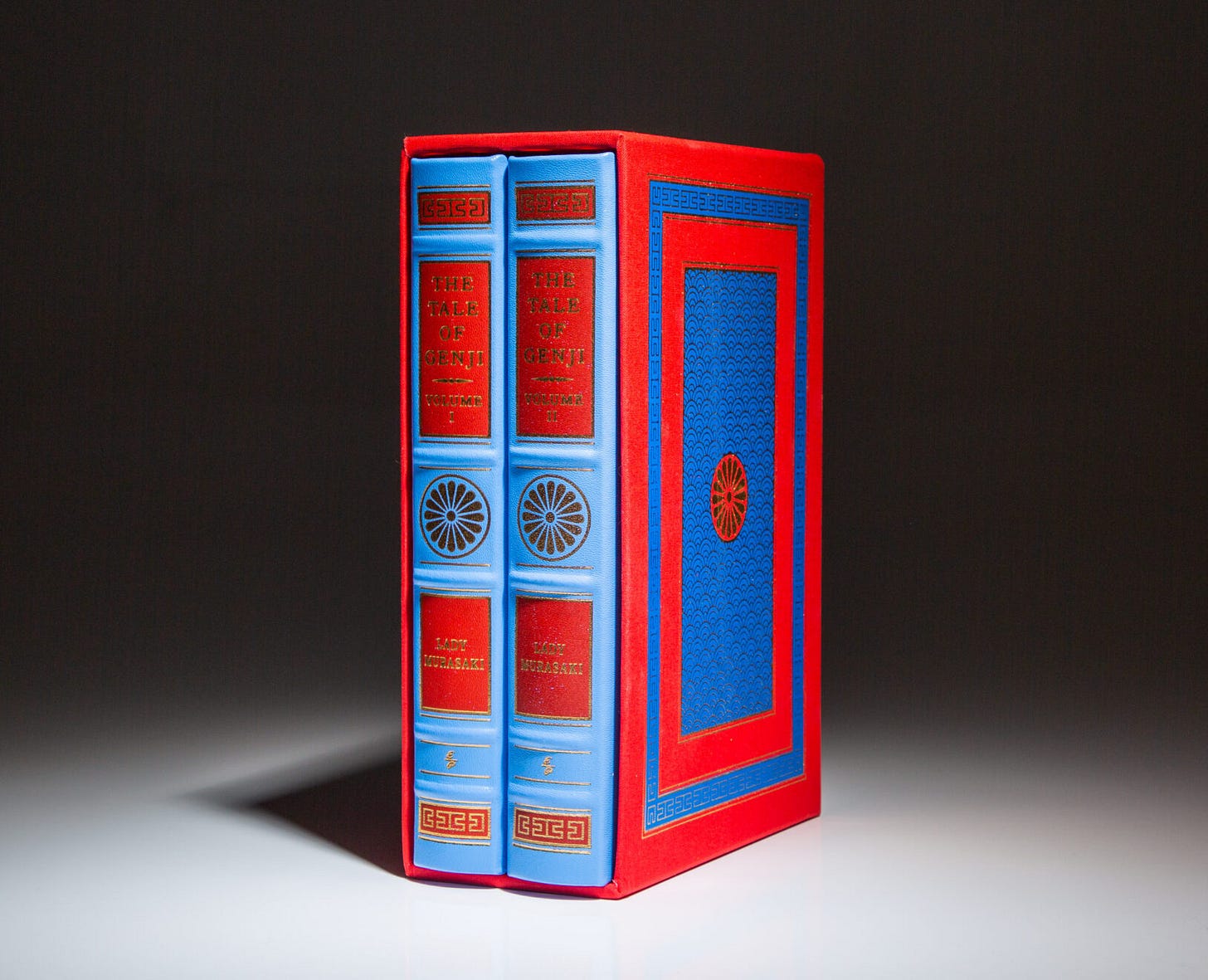

The two translations we have the ability to utilize for the Library edition are the Castalia (T2) and Waley (T1) translations, and since most people preferred the former, and because Easton Press already has a lovely two-volume leather set of the latter available, we will be utilizing our own Translation 2 for the Castalia Library edition.

Now, for those who might have any concerns about the fidelity of the Castalia translation, let me hasten to remind you that the above analyses were based on a relatively short set of 19 lines of kanji. It is absolutely not a reliable measure of fidelity across the thousands of lines that comprise the entire work; for example, in his 1933 translation, Waley leaves out all 110 lines of chapter 38, Suzumoshi, entirely “due to his belief that it was not essential to the overall narrative.”

When the initial translation is complete, we will perform a similar analysis of textual fidelity across the entirety of all the translations. My expectation, on the basis of the chapters completed to date, is that it will come in second, behind Tyler (2009), whose primary focus was textual fidelity for an academic translation and was not particularly concerned about literary quality.

Don’t forget that our translation is very far from finished. So once we complete the first draft, we will do another iteration to tighten the textual fidelity without losing any of the literary quality achieved. We’ve already done one experiment in this regard that appears to be very promising.

Not only that, but we have very good reason to believe that the approach we are taking with the hundreds of waka is not only going to be much, much better than any of the previous translations, but may even be considered revolutionary in its effect.

For those interested in a deeper and more substantive analysis, here is one covering the entirety of one of the more famous and important chapters, Yugao. The chapter is so long that Deepseek couldn’t even accomplish the job, so this is from Claude 4.5 Sonnet.

Fidelity Ranking (most to least faithful)

T4 — Closest to the source in structure and detail; scholarly precision

T3 — Highly accurate with minor interpretive liberties

T5 — Generally accurate but occasionally explanatory

T1 — Significant expansion and omission; interpretive freedom

T2 — Substantial departures from source; extensive invention

Literary Quality Ranking (highest to lowest)

T2 — Most accomplished prose; psychological depth; contemporary literary register

T4 — Elegant and controlled; captures Heian atmosphere

T3 — Clean and readable; occasionally flat

T5 — Accessible but somewhat prosaic; lacks distinction

T1 — Dated register; occasionally stilted; excessive ornamentation

Overall Preference Ranking

T2 — Despite fidelity concerns, the most compelling reading experience

T4 — Best balance of accuracy and literary quality

T3 — Reliable and competent; lacks memorable voice

T5 — Serviceable but undistinguished

T1 — Historical interest only; too distant from contemporary literary expectations

Comparative Assessment: Key Passages

The Fan Poem

Original import: A woman has sent a poem via a white fan, punning on the evening-face flower and suggesting she perceives Genji’s radiance.

Winner: T2 for compression and ambiguity; T4 for accuracy.

The Death Scene

This is the emotional center of the chapter—the moment when Genji realizes his lover has died beside him.

Winner: T2 for emotional power; T4 for balanced treatment.

Summary

T1

A pioneering translation now of primarily historical interest. The Edwardian register, while once innovative, now distances readers. The translator’s tendency to explain and expand reduces the mystery of the original. Poetry is weak. Recommended only for those interested in translation history.

T2

A remarkable literary achievement that must be evaluated on two axes. As English prose, it is superb—psychologically acute, rhythmically controlled, emotionally devastating. As translation, it is problematic—the invention of material, the interpretive interventions, the restructuring of scenes all raise questions about fidelity. Those who prioritize reading experience over strict accuracy will find this the most rewarding text.

T3

A solid, reliable translation that respects the source and communicates its meaning clearly. It lacks the distinctive voice that would make it memorable as literature, but it also lacks the distortions of T1’s expansions or T2’s inventions. Recommended for readers who want accuracy without scholarly apparatus.

T4

The best all-around translation, balancing fidelity and literary quality. The prose is elegant without being showy, the scholarship is evident but unobtrusive, and the translator’s respect for the source’s ambiguities is admirable. The footnotes may interrupt reading flow, but they provide context without interpolating explanatory material into the text. Recommended for serious readers who want both accuracy and art.

T5

An accessible, contemporary translation that prioritizes clarity and readability. The prose is competent but rarely rises to distinction. Cultural context is handled through brief explanations that sometimes feel pedagogical. Recommended for first-time readers who want an easy entry point, but not for those seeking a literary experience.

Now, one thing those who favored T1 over T2 should keep in mind: that archaic stylistic voice that appeals to you has absolutely nothing to do with Heian Japan or the original voice of the author. That’s what the AI was describing as the “Edwardian register”. It’s from the England of 100 years ago, not the Heian Japan of 1,300 years before that, and the voice you’re hearing is Arthur Waley’s, not Lady Murasaki’s. Arthur Waley’s accomplishment was truly incredible, but he didn’t speak Japanese, he never visited Japan, and although he did teach himself how to read kanji to a near-fluent level, he invented a fair amount of the detail that provides the color to his translation.

Ironically, given my familiarity with the country, the culture, the language, and the literature, I am far better-equipped and even better-credentialed to make reasonable decisions about filling in the various literary blanks than Arthur Waley ever was. I’m not criticizing his decisions; I even have three different editions of his translation, which I have read twice. I consider his work a masterpiece. I’m simply pointing out the facts for the benefit of those who have no reason to know them.

For example, all of the famous names that he utilized, from To no Chujo to Fujitsubo and Yugao and so forth, the famous names that are utilized in the other translations too, don’t even exist in the original Japanese text. Waley simply invented all of them. Genji’s friend, rival, and brother-in-law, To no Chujo, is actually THE Tō no Chūjō, or the High Middle Captain. It’s a noble rank, not a name. Most of the female names Waley provided the characters are based on the descriptors that Murasaki uses in the scenes in which they appear, such as the Lady of the Cicada Shell or the Lady of the Evening Faces. In the original text, it’s only the servants who are occasionally named; the nobility are, for the most part, nameless throughout.

Can you imagine if we simply assigned them names like Jim-Bob and Suzy because it made it easier for the reader to keep track of them? That’s literally what Waley did, and the other translators have tended to follow his lead. How can that be considered faithful to the text?

Whereas most of the “invention” and lack of textual fidelity described in the T2 translation is nothing more than the revelation of the implicit. For example, while the line “They did not know they were praying for a ghost” is absent from the original text, what is explicitly described in the text is how the servant women are praying for the safe return of their lady whom the reader knows is dead, whose death has also been explicitly portrayed by Murasaki. So the invented line is implicit in the text and adds to the psychological weight of the scene by highlighting the futility of the serving ladies’ efforts on the dead girl’s behalf.

As for the restructuring of scenes, what that refers to is arranging to make it clear who is speaking and who is being referred to. The literal translation can be worse than opaque in this regard, it can be confusing and incoherent by muddling who is speaking, who is being spoken to, and to whom the speech refers.

There is no need for a perfectly literal translation. Google Translate can provide that, and Tyler has already delivered the academic version of it, which is T4. But the problem is this: just as with speaking a foreign language, literal accuracy is not the same thing as literary, emotional, or psychological accuracy. So the prime objective of the T2 translation is to deliver an emotional, psychological, and literary experience for the English reader that is closer to the experience of the Japanese reader. Note that the modern Japanese texts don’t use Waley’s invented names either, with the exception of two back-translations.

Some will frown upon this approach. Others, we hope, will praise it. But regardless, the main reason for us to do it this way is to deliver a highly readable Genji Monogatari that is true to the text in its own way without sounding like its predecessors. The fact that so many people genuinely preferred our translation to the existing ones, even prior to its final polishing, tends to indicate we are on the right artistic track.

And only time will tell.

The other advantage of T2, of course, is this: being the first edition of a unique and original translation of Genji Monogatari will only make the Library editions all the more collectible and therefore valuable to the subscribers.

But regardless, at Castalia, we follow our aesthetic and artistic imperatives, not the unwritten rules set forth by authorities we neither recognize nor respect. Or, to put it in terms appropriate to the project:

"that archaic stylistic voice that appeals to you has absolutely nothing to do with Heian Japan or the original voice of the author"

I am happy to have been wrong. Of course T1's voice would have appealed to me bc of its familiar tone. But leaving out a whole chapter is criminal, and does a disservice to the author. Faithfulness to the text is one thing but making the prose sound good while trying to convey the same emotional meanings is another. I am looking forward to this new translation.

The Edwardian register is nice regardless of its faithfulness to the original Japanese, but on the other hand leaving out a whole chapter because it's "not essential"?!

Oh dear.