STUDIES IN THE NAPOLEONIC WARS 100

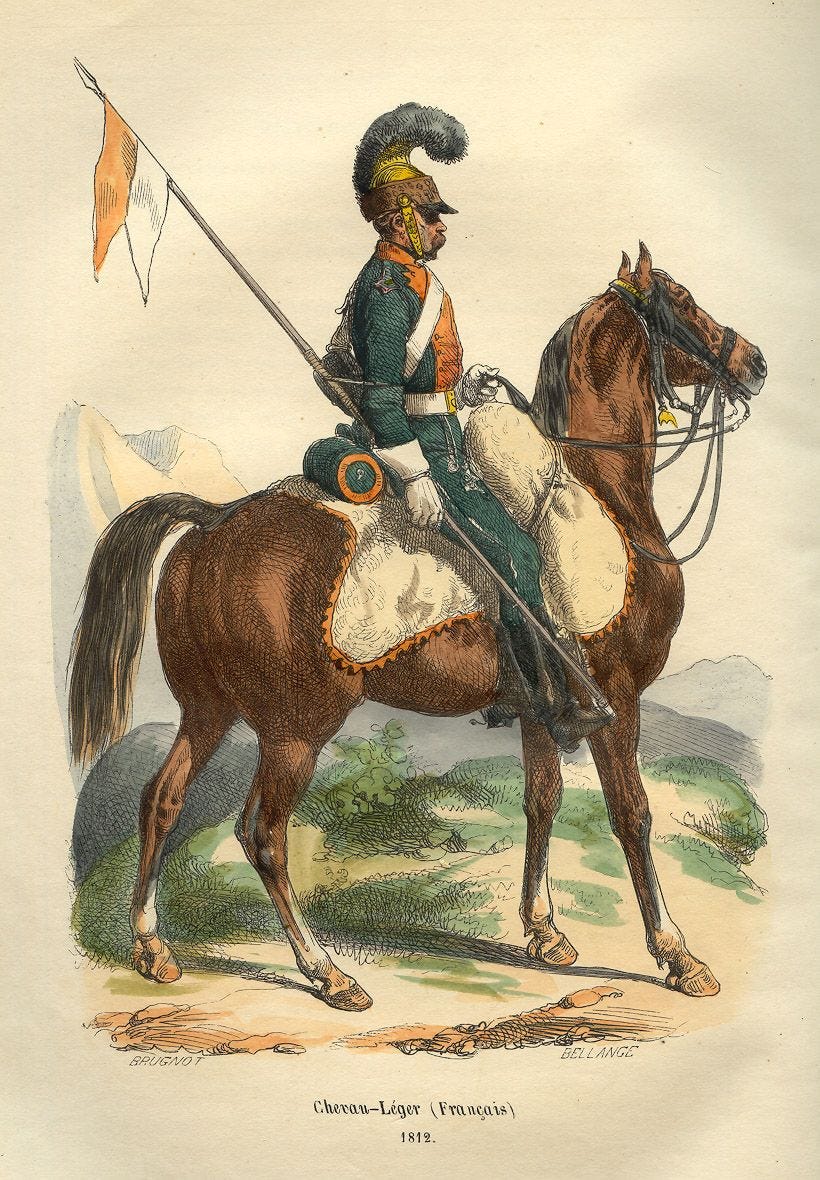

Les Chevaux Légers Lanciers

12. Les Chevaux Légers Lanciers (8)

It remains to speak of one more class of cavalry which was introduced into the imperial army so late as June 18, 1811, the lancers, or chevaux légers lanciers, as they were technically called. Down to this date the only regular regiment armed with the lance in the French army was that Polish regiment, the “Lancers of the Vistula”, which is too well remembered by English students of military history for the havoc that it made on Colborne’s brigade at Albuera. But Napoleon had also other Polish auxiliary regiments serving him, which did not belong to his own army but to the contingents supplied to him by the “Grand Duchy of Warsaw”, as he styled that Polish state which he had created in 1807. There had been no lancers in the French hosts since the XVIth century, though the great Maurice de Saxe had vainly tried to get them introduced in the time of Louis XV. Indeed, the lance was nowhere used in Europe from 1600 down to the very end of the XVIIIth century save among the Poles. The few regiments of Uhlans (the word is Polish) which were to be found in the Austrian and Prussian armies about 1800 were all embodied from the Polish subjects of those powers.

Napoleon’s tardy recognition of the virtues of the lance in 1811 was entirely due to the good service which he had seen his Polish auxiliaries do with it, especially at Wagram. He formed nine regiments of lancers of the line, by transforming old existing corps into lance-regiments, telling off six regiments of French dragoons, one of chasseurs, and the old “Lancers of the Vistula” to form the new category of troops.

The dragoon regiments at first preserved their old uniform, the brass helmet and high boots, but later all the nine regiments armed with the lance adopted the Polish style of dress, with the square-topped lancer cap, the tight tunic, and long breeches reaching to the ankle with short boots.

The particular profit which the Emperor hoped to get from the introduction of this new sort of cavalry into the service seems to have been, to a certain extent, that which was foreseen in the early XXth century from the giving of the lance to at least the first rank in cavalry of all sorts all over Europe. I mean the advantage of increased effectiveness of shock in combats between cavalry and cavalry acting in mass, when one side opposes the longer weapon to an enemy not provided with it. But there was another reason which acted in 1811, though it is of little importance now—the superiority of the lance over the sabre in attacking infantry in square, who have exhausted their fire, and are relying on the bayonet alone for keeping off advancing cavalry.

For the length of the lance being greater than that of the musket and bayonet, it was possible to use it effectively against men standing in square, when the sabre could not reach them. Not only did raw or shaken infantry often waste the whole of their fire simultaneously against charging cavalry, so that when the volleys of all the ranks had been delivered the survivors of the charge found no rear rank of men loaded ready for them, but another consideration had to be remembered. With the musket of those days, heavy rain damped the powder and clogged the pan, so that occasions were known where not one piece out of four went off, when the command to fire was given. In such a case the square had to rely on its bayonets alone for keeping away the cavalry, which came up against it almost intact.

To obtain a deluxe leatherbound edition of STUDIES ON THE NAPOLEONIC WARS, subscribe to Castalia History.