THE ART OF WAR IN THE MIDDLE AGES 65

The Tactical Disaster of Poictiers, 1356

6.8. The Tactical Disaster of Poictiers, 1356

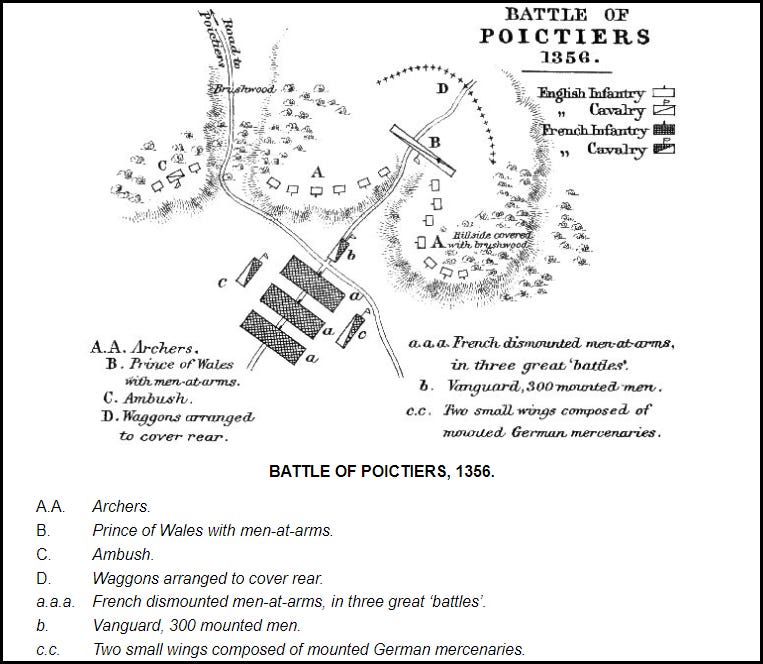

Bearing this in mind, King John, at the battle of Poictiers, resolved to imitate the successful expedient of King Edward. He commanded the whole of his cavalry, with the exception of two corps, to shorten their spears, take off their spurs, and send their horses to the rear. He had failed to observe that the circumstances of attack and defence are absolutely different. Troops who intend to root themselves to a given spot of ground adopt tactics the very opposite of those required for an assault on a strong position. The device which was well chosen for the protection of Edward’s flanks at Creçy, was ludicrous when adopted as a means for storming the hill of Maupertuis. Vigorous impact and not stability was the quality at which the king should have aimed. Nothing, indeed, could have been more fatal than John’s conduct throughout the day. The battle itself was most unnecessary, since the Black Prince could have been starved into surrender in less than a week. If, however, fighting was to take place, it was absolutely insane to form the whole French army into a gigantic wedge--where corps after corps was massed behind the first and narrowest line--and to dash it against the strongest point of the English front. This, however, was the plan which the king determined to adopt. The only access to the plateau of Maupertuis lay up a lane, along whose banks the English archers were posted in hundreds. Through this opening John thrust his vanguard, a chosen body of 300 horsemen, while the rest of his forces, three great masses of dismounted cavalry, followed close behind.

It is needless to say that the archers shot down the greater part of the advanced corps, and sent the survivors reeling back against the first ‘battle’ in their rear. This at once fell into disorder, which was largely increased when the archers proceeded to concentrate their attention on its ranks. Before a blow had been struck at close quarters, the French were growing demoralized under the shower of arrows. Seeing his opportunity, the Prince at once came down from the plateau, and fell on the front of the shaken column with all his men-at-arms. At the same moment a small ambuscade of 600 men, which he had placed in a wood to the left, appeared on the French flank. This was too much for King John’s men: without waiting for further attacks about two-thirds of them left the field. A corps of Germans in the second ‘battle’ and the troops immediately around the monarch’s person were the only portions of the army which made a creditable resistance. The English, however, were able to surround these bodies at their leisure, and ply bow and lance alternately against them till they broke up. Then John, his son Philip, and such of his nobles as had remained with him, were forced to surrender.

This was a splendid tactical triumph for the Prince, who secured the victory by the excellence of the position he had chosen, and the judicious use made of his archery. John’s new device for attacking an English army had failed, with far greater ignominy than had attended the rout of his predecessor’s feudal chivalry at Creçy.

To obtain a deluxe leatherbound edition of THE ART OF WAR IN THE MIDDLE AGES by Sir Charles Oman, subscribe to Castalia History.

For questions about subscription status and billings: subs@castalialibrary.com

For questions about shipping and missing books: castaliashipping@gmail.com

You can now follow Castalia Library on Instagram as well.