THE ART OF WAR IN THE MIDDLE AGES 68

The Battle of Agincourt

6.11. The Battle of Agincourt

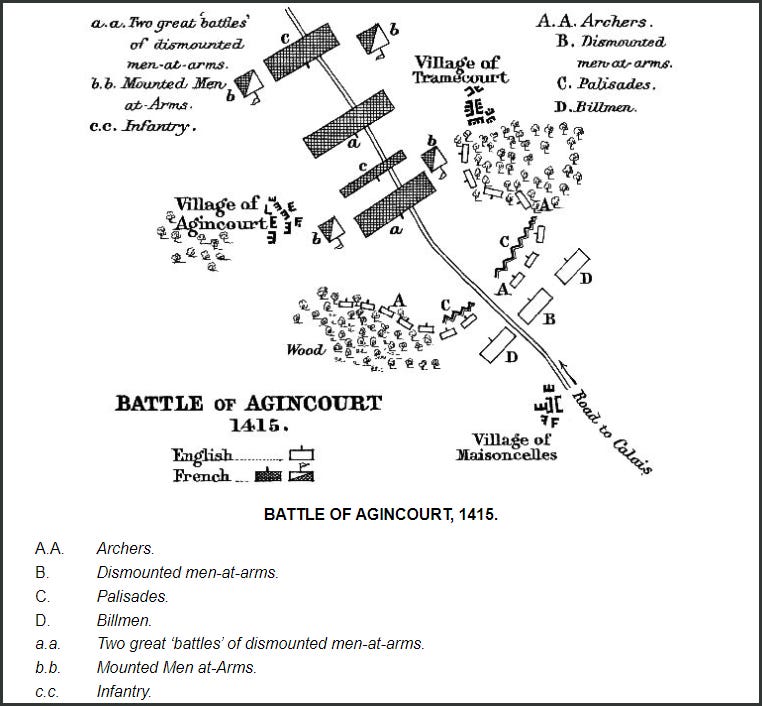

At eleven o’clock the French began to move towards the English position: presently they passed the village of Agincourt, and found themselves between the woods, and in the ploughed land. Struggling on for a few hundred yards, they began to sink in the deep clay of the fields: horsemen and dismounted knight alike found their pace growing slower and slower. By this time the English archery was commencing to play upon them, first from the front, then from the troops concealed in the woods also. Pulling themselves together as best they could, the French lurched heavily on, sinking to the ankle or even to the knee in the sodden soil.

Not one in ten of the horsemen ever reached the line of stakes, and of the infantry not a man struggled on so far. Stuck fast in the mud they stood as a target for the bowmen, at a distance of from fifty to a hundred yards from the English front. After remaining for a short time in this unenviable position, they broke and turned to the rear. Then the whole English army, archers and men-at-arms alike, left their position and charged down on the mass, as it staggered slowly back towards the second ‘battle.’ Perfectly helpless and up to their knees in mire, the exhausted knights were cast down, or constrained to surrender to the lighter troops who poured among them, ‘beating upon the armour as though they were hammering upon anvils.’

The few who contrived to escape, and the body of arbalesters who had formed the rear of the first line, ran in upon the second ‘battle,’ which was now well engaged in the miry fields, just beyond Agincourt village, and threw it into disorder. Close in their rear the English followed, came down upon the second mass, and inflicted upon it the fate which had befallen the first. The infantry-reserve very wisely resolved not to meddle with their masters’ business, and quietly withdrew from the field.

Few commanders could have committed a more glaring series of blunders than did the Constable: but the chief fault of his design lay in attempting to attack an English army, established in a good position, at all. The power of the bow was such that not even if the fields had been dry, could the French army have succeeded in forcing the English line. The true course here, as at Poictiers, would have been to have starved the king, who was living merely on the resources of the neighbourhood, out of his position. If, however, an attack was projected, it should have been accompanied by a turning movement round the woods, and preceded by the use of all the arbalesters and archers of the army, a force which we know to have consisted of 15,000 men.

Such a day as Agincourt might have been expected to break the French noblesse of its love for an obsolete system of tactics. So intimately, however, was the feudal array bound up with the feudal scheme of society, that it yet remained the ideal order of battle. Three bloody defeats, Crevant, Verneuil, and the ‘Day of the Herrings,’ were the consequences of a fanatical adherence to the old method of fighting. On each of those occasions the French columns, sometimes composed of horsemen, sometimes of dismounted knights, made a desperate attempt to break an English line of archers by a front attack, and on each occasion they were driven back in utter rout.

To obtain a deluxe leatherbound edition of THE ART OF WAR IN THE MIDDLE AGES by Sir Charles Oman, subscribe to Castalia History.

For questions about subscription status and billings: subs@castalialibrary.com

For questions about shipping and missing books: castaliashipping@gmail.com

You can now follow Castalia Library on Instagram as well.