THE ART OF WAR IN THE MIDDLE AGES 61

Bannockburn and the Misuse of Missile Troops

6.4. Bannockburn and the Misuse of Missile Troops

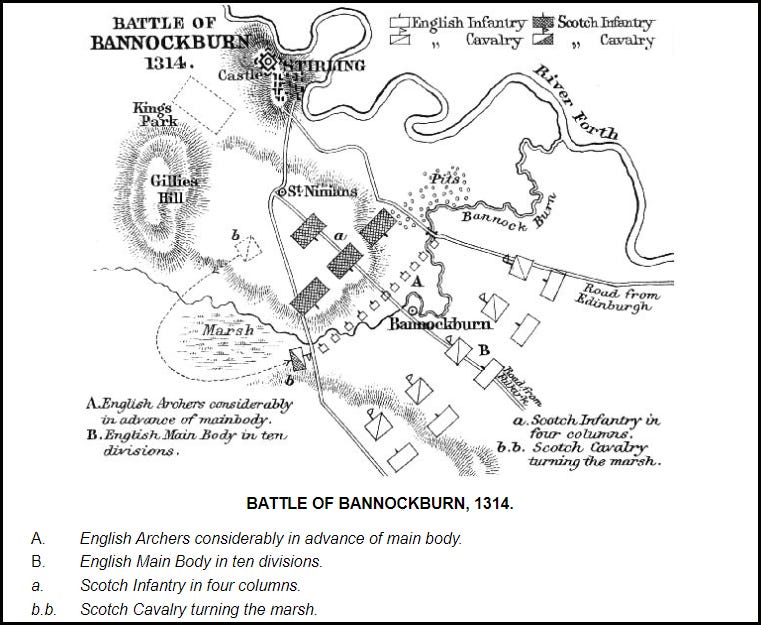

Bannockburn, indeed, forms a notable exception to the general rule. Its result, however, was due not to an attempt to discard the tactics of Falkirk, but to an unskilful application of them. The forces of Robert Bruce, much like those of Wallace in composition, consisted of 40,000 pikemen, a certain proportion of light troops, and less than 1000 cavalry. They were drawn up in a very compact position, flanked by marshy ground to the right, and to the left by a quantity of small pits destined to arrest the charge of the English cavalry. Edward II refrained from any attempt to turn Bruce’s army, and by endeavouring to make 100,000 men cover no more space in frontage than 40,000, cramped his array, and made manœuvres impossible.

His most fatal mistake, however, was to place all his archers in the front line, without any protecting body of horsemen. The arrows were already falling among the Scotch columns before the English cavalry had fully arrived upon the field. Bruce at once saw his opportunity: his small body of men-at-arms was promptly put in motion against the bowmen. A front attack on them would of course have been futile, but a flank charge was rendered possible by the absence of the English squadrons, which ought to have covered the wings. Riding rapidly round the edge of the morass, the Scotch horse fell on the uncovered line, rolled it up from end to end, and wrought fearful damage by their unexpected onset. The archers were so maltreated that they took no further effective part in the battle.

Enraged at the sudden rout of his first line, Edward flung his great masses of cavalry on the comparatively narrow front of the Scotch army. The steady columns received them, and drove them back again and again with ease. At last every man-at-arms had been thrown into the mêlée, and the splendid force of English horsemen had become a mere mob, surging helplessly in front of the enemy’s line, and executing partial and ineffective charges on a cramped terrain. Finally, their spirit for fighting was exhausted, and when a body of camp-followers appeared on the hill behind Bruce’s position, a rumour spread around that reinforcements were arriving for the Scots. The English were already hopeless of success, and now turned their reins to retreat. When the Scotch masses moved on in pursuit, a panic seized the broken army, and the whole force dispersed in disorder. Many galloped into the pits on the left; these were dismounted and slain or captured. A few stayed behind to fight, and met a similar fate. The majority made at once for the English border, and considered themselves fortunate if they reached Berwick or Carlisle without being intercepted and slaughtered by the peasantry.

The moral of the day had been that the archery must be adequately supported on its flanks by troops capable of arresting a cavalry charge. The lesson was not thrown away, and at Creçy and Maupertuis the requisite assistance was given, with the happiest of results.

To obtain a deluxe leatherbound edition of THE ART OF WAR IN THE MIDDLE AGES by Sir Charles Oman, subscribe to Castalia History.

For questions about subscription status and billings: subs@castalialibrary.com

For questions about shipping and missing books: castaliashipping@gmail.com

You can now follow Castalia Library on Instagram as well.