THE ART OF WAR IN THE MIDDLE AGES 49

The Battle of Granson

5.13. The Battle of Granson

From that day the Confederates were able to reckon their reputation for obstinate and invincible courage, as one of the chief causes which gave them political importance. The generals and armies who afterwards faced them, went into battle without full confidence in themselves. It was no light matter to engage with an enemy who would not retire before any superiority in numbers, who was always ready for the fight, who would neither give nor take quarter. The enemies of the Swiss found these considerations the reverse of inspiriting before a combat: it may almost be said that they came into the field expecting a defeat, and therefore earned one.

This fact is especially noticeable in the great Burgundian war. If Charles the Rash himself was unawed by the warlike renown of his enemies, the same cannot be said of his troops. A large portion of his motley army could not be trusted in any dangerous crisis: the German, Italian, and Savoyard mercenaries knew too well the horrors of Swiss warfare, and shrank instinctively from the shock of the phalanx of pikes. The duke might range his men in order of battle, but he could not be sure that they would fight. The old proverb that ‘God was on the side of the Confederates’ was ever ringing in their ears, and so they were half beaten before a blow was struck.

Charles had endeavoured to secure the efficiency of his army, by enlisting from each warlike nation of Europe the class of troops for which it was celebrated. The archers of England, the arquebusiers of Germany, the light cavalry of Italy, the pikemen of Flanders, marched side by side with the feudal chivalry of his Burgundian vassals. But the duke had forgotten that, in assembling so many nationalities under his banner, he had thrown away the cohesion which is all-important in battle. Without mutual confidence or certainty that each comrade would do his best for the common cause, the soldiery would not stand firm. Granson was lost merely because the nerve of the infantry failed them at the decisive moment, although they had not yet been engaged.

In that fight the unskilful generalship of the Swiss had placed the tactical advantages on the side of Charles: he had both outflanked them and attacked one division of their army before the others came up. He had, however, to learn that an army superior in morale and homogeneity, and thoroughly knowing its weapon, may be victorious in spite of all disadvantages.

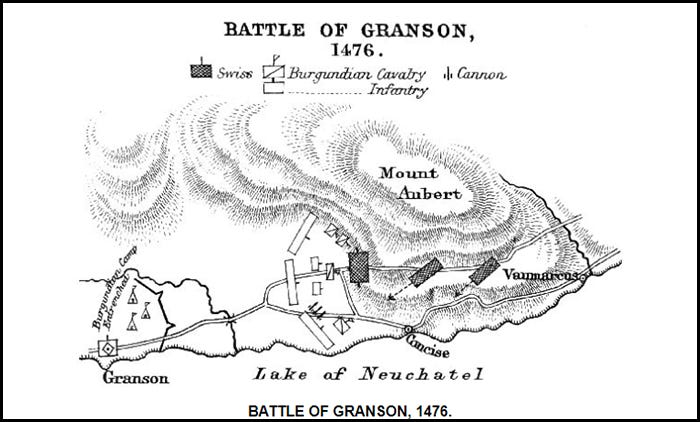

Owing to their eagerness for battle the Confederate vanguard, composed of the troops of Bern, Freiburg, and Schwytz, had far outstripped the remainder of the force. Coming swiftly over the hill side in one of their usual deep columns, they found the whole Burgundian army spread out before them in battle array on the plain of Granson. As they reached the foot of the hill they at once saw that the duke’s cavalry was preparing to attack them. Old experience had made them callous to such sights: facing outwards the column awaited the onset.

The first charge was made by the cavalry of Charles’ left wing: it failed, although the gallant lord of Chateauguyon, who led it, forced his horse among the pikes and died at the foot of the Standard of Schwytz. Next the duke himself led on the lances of his guard, a force who had long been esteemed the best troops in Europe: they did all that brave men could, but were dashed back in confusion from the steady line of spear-points. The Swiss now began to move forward into the plain, eager to try the effect of the impact of their phalanx on the Burgundian line. To meet this advance Charles determined to draw back his centre, and when the enemy advanced against it, to wheel both his wings round upon their flank. The manœuvre appeared feasible, as the remainder of the Confederate army was not yet in sight. Orders were accordingly sent to the infantry and guns who were immediately facing the approaching column, directing them to retire; while at the same time the reserve was sent to strengthen the left wing, the body with which the duke intended to deliver his most crushing stroke.

The Burgundian army was in fact engaged in repeating the movement which had given Hannibal victory at Cannæ: their fortune, however, was very different. At the moment when the centre had begun to draw back, and when the wings were not yet engaged, the heads of the two Swiss columns, which had not before appeared, came over the brow of Mont Aubert; moving rapidly towards the battlefield with the usual majestic steadiness of their formation. This of course would have frustrated Charles’ scheme for surrounding the first phalanx; the échelon of divisions, which was the normal Swiss array, being now established.

The aspect of the fight, however, was changed even more suddenly than might have been expected. Connecting the retreat of their centre with the advance of the Swiss, the whole of the infantry of the Burgundian wings broke and fled, long before the Confederate masses had come into contact with them. It was a sheer panic, caused by the fact that the duke’s army had no cohesion or confidence in itself; the various corps in the moment of danger could not rely on each others’ steadiness, and seeing what they imagined to be the rout of their centre, had no further thought of endeavouring to turn the fortune of the day.

It may be said that no general could have foreseen such a disgraceful flight; but at the same time the duke may be censured for attempting a delicate manœuvre with an army destitute of homogeneity, and in face of an enterprising opponent. ‘Strategical movements to the rear’ have always a tendency to degenerate into undisguised retreats, unless the men are perfectly in hand, and should therefore be avoided as much as possible. Granson was for the Swiss only one more example of the powerlessness of the best cavalry against their columns: of infantry fighting there was none at all.

To obtain a deluxe leatherbound edition of THE ART OF WAR IN THE MIDDLE AGES by Sir Charles Oman, subscribe to Castalia History.

For questions about subscription status and billings: subs@castalialibrary.com

For questions about shipping and missing books: castaliashipping@gmail.com

You can now follow Castalia Library on Instagram as well.