THE ART OF WAR IN THE MIDDLE AGES 30

The Supremacy of Feudal Cavalry

4.1. The Supremacy of Feudal Cavalry

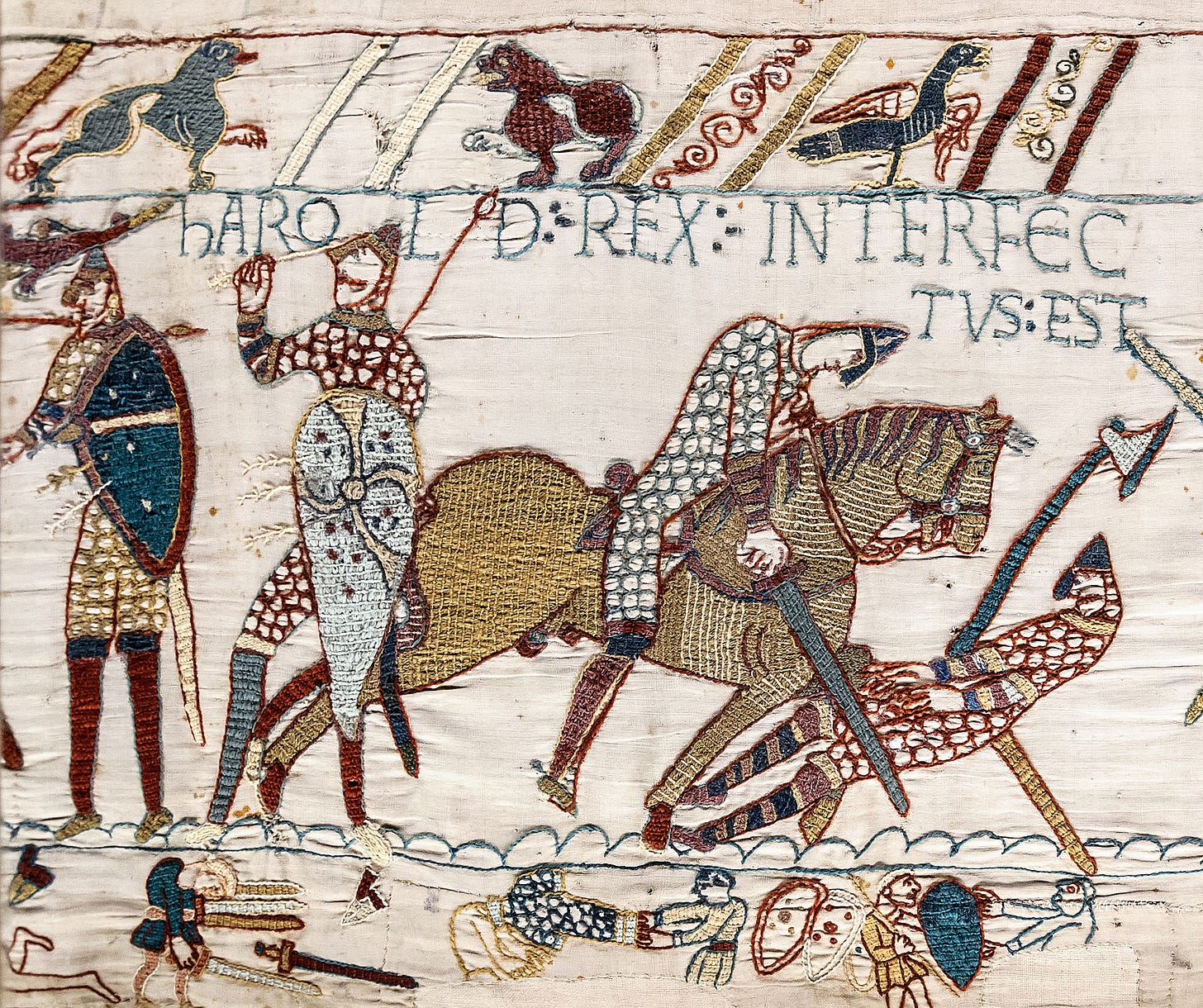

From the battle of Hastings to the battles of Morgarten and Cressy.

A.D. 1066–1346.

Between the last struggles of the infantry of the Anglo-Dane, and the rise of the pikemen and bowmen of the fourteenth century lies the period of the supremacy of the mail-clad feudal horseman. The epoch is, as far as strategy and tactics are concerned, one of almost complete stagnation: only in the single branch of Poliorcetics does the art of war make any appreciable progress.

The feudal organization of society made every person of gentle blood a fighting man, but it cannot be said that it made him a soldier. If he could sit his charger steadily, and handle lance and sword with skill, the horseman of the twelfth or thirteenth century imagined himself to be a model of military efficiency. That discipline or tactical skill may be as important to an army as mere courage, he had no conception. Assembled with difficulty, insubordinate, unable to manœuvre, ready to melt away from its standard the moment that its short period of service was over, a feudal force presented an assemblage of unsoldierlike qualities such as has seldom been known to coexist.

Primarily intended to defend its own borders from the Magyar, the Northman, or the Saracen, the foes who in the tenth century had been a real danger to Christendom, the institution was utterly unadapted to take the offensive. When a number of tenants-in-chief had come together, each blindly jealous of his fellows and recognizing no superior but the king, it would require a leader of uncommon skill to persuade them to institute that hierarchy of command, which must be established in every army that is to be something more than an undisciplined mob. Monarchs might try to obviate the danger by the creation of offices such as those of the Constable and Marshal, but these expedients were mere palliatives.

The radical vice of insubordination continued to exist. It was always possible that at some critical moment a battle might be precipitated, a formation broken, a plan disconcerted, by the rashness of some petty baron or banneret, who could listen to nothing but the promptings of his own heady valour. When the hierarchy of command was based on social status rather than on professional experience, the noble who led the largest contingent or held the highest rank, felt himself entitled to assume the direction of the battle. The veteran who brought only a few lances to the array could seldom aspire to influencing the movements of his superiors.

To obtain a deluxe leatherbound edition of THE ART OF WAR IN THE MIDDLE AGES by Sir Charles Oman, subscribe to Castalia History.

For questions about subscription status and billings: subs@castalialibrary.com

For questions about shipping and missing books: castaliashipping@gmail.com

You can now follow Castalia Library on Instagram as well.